About Us

Exhibits

Photos

Membership

Business

Sponsors

Donations

Gift Shop

Contact

Links

~ ~ ~

James R.

McConnell

Page

Robert H.

Upchurch Page

~ ~ ~

Memorial

Brick

Campaign

~ ~ ~

THE LIGHT TOWER

"General Aviation News" Article

Here

The Development of

Night Navigation in the U.S.

Since September 1920, the Post Office Dept. had flown the mail from New York to San Francisco, but during daytime only, transferring it to trains at night. As a result, elapsed time was 72 hours at best, or a mere 36-hour saving over the fastest all-rail trip.

Flying the mail was risky business. During the nine years the Post Office Department operated the Airmail Service, there were over 6,500 forced landings. On the average, airmail pilots had a life span of only about 900 flying hours.

The Post Office Dept. increased the pressure on its pilots by announcing that the air mail flights could be conducted on a schedule 93% of the time.

Flying in open-cockpit biplanes, exposed to the bitterly cold air and harsh weather conditions, the pilots often became so numbed and exhausted that they couldn't think clearly or make decisions quickly. Not publicized by the Post Office Dept. was the fact that in order to fight the cold and the constant pressure of deadlines, with on-time delivery expected under even the worst of flying conditions, many of the pilots carried bottles of liquor along when they flew.

Carrying the mail was not the only business of aviation. In 1914 the world's first regularly scheduled air-passenger service opened up along a 22-mile route from Tampa to St. Petersburg, Florida. The service could carry only one passenger at a time and cost $5 for the 23-minute flight. It was a financial failure and lasted only a short time.

These early days of aviation presented a unique set of problems and the inability of aircraft to navigate in rough weather and darkness topped the list. The government became involved in 1926.

![]()

The beacons, of course, did not flash, but rotated through a complete circle giving the impression of flashing.

In October 1931, D. C. Young of the Airways Lighting Sub-Committee recapped the progress of lighted airways at a lighting conference in Pittsburgh, Pa.

"Ten years ago, a scheduled night flight by airplane across the United States was only a dream. Now, such flights occur nightly, and on scheduled time. The converting of this hazardous journey into one of comparative safety ... is the achievement of constructing aerial highways for the airman.

If air travel were confined to daylight hours only, the speed and directness of route would give the airplane little or no advantage over fast trains operating on 24-hour schedules. The Post Office Dept. realized this in 1922 when it was transporting the mail by air. So it established facilities for the airmail pilot to follow at night and succeeded in showing a remarkable improvement in speed on the coast-to-coast route.

In the four years since 1926 when the government took over the airways 14,500 miles of lighted highways had been created for the airmen.

High-intensity beacons are established approximately 10 miles apart along these civil airways . The beacon consists of a 24-inch parabolic mirror and a 110-volt, 1000 watt lamp. The beacons, which rotate at 6 rpm, show a one-million candlepower flash every 10 seconds for 1/10th second duration.

Pilots often stopped at McGirr Field, on the OmahaĖChicago route, when they had an "emergency," knowing that the food was excellent and that they would be well cared for.

Intermediate landing fields are provided every 30 miles along these routes, in the absence of suitable commercial or municipal fields, and each is equipped with beacon, boundary, approach, obstruction, and wind-cone lights.

![]()

![]()

Two course lights are mounted on the tower just below each searchlight; one points forward along the airway and the other points backward. These 500-watt searchlights give a 15 degree horizontal beam width.

The course lights are fitted with either red or green lenses. Every third beacon has green course lights signifying that it is on an intermediate landing field. Thus the pilot knows at a long range the availability of landing fields. (This is the forerunner of todayís airport rotating beacons which alternately flash green and white.)

All other beacons had red course lights.

As the mechanism revolved and the clear flash of the beacon passed from the pilotís vision, the red or green flash of the course light came into view. Course lights flashed coded dot-dash signals to indicate the beaconís position on the airway. Code signals ran from 0 to 9; thus, if a pilot received a signal for the number 4, he knew he was flying over the fourth beacon of a particular 100-mile stretch of airway. But he could not determine his precise position merely by receiving a course-light signal if he did not know independently over which 100-mile stretch he was flying.

![]() Letters designated the airways, the first letters of their terminal

cities. The order of the letters was established as south to north and

west to east. Thus Omaha to Chicago was Airway O-C. LA-SF defined the

Los Angeles to San Francisco airway, and so forth.

Letters designated the airways, the first letters of their terminal

cities. The order of the letters was established as south to north and

west to east. Thus Omaha to Chicago was Airway O-C. LA-SF defined the

Los Angeles to San Francisco airway, and so forth.

Regular maintenance of the airway beacons and intermediate fields was crucial. This duty was entrusted to Airway Caretakers. Daily they climbed the 51-ft. steel towers to check every beacon within their territory, cleaned dirty lenses, replaced burned-out bulbs, etc. Repair problems requiring more expertise or equipment and tools not locally available were referred to "mechanicians," who serviced a 175-mile route with a half-ton pickup truck.

Caretakers at intermediate fields were on duty from 6:00 pm to 6:00 am. If a pilot "dropped" in to one of these emergency fields, caretakers were expected to provide transportation to and from town, furnish them with meals, and assist in repairing their aircraft.

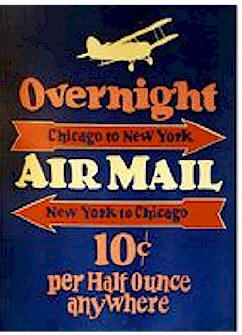

To "Plane Post" a letter cost 24 cents an ounce in 1918, which included special delivery.

With airways on the transcontinental route now lighted, airmail could be delivered in one-third the time of a train.

"General Aviation News" Article Here

We Gratefully Thank and Acknowledge Our Generous Sponsors

Copyright James R.

McConnell Air Museum Inc. - 2014 - All Rights Reserved

Web Design by Plank Road Consulting -

www.plankroadconsulting.com